Initiative

Initiative

Initiative

Initiative

Developed and designed for Alberta producers, the Habitat and Biodiversity Assessment Tool is now part of the Habitat Management Chapter in the Environmental Farm Plan. The tool was created to build awareness and help you learn about how stewardship opportunities can impact biodiversity and the habitat of all species, especially those at risk that may exist on your lands.

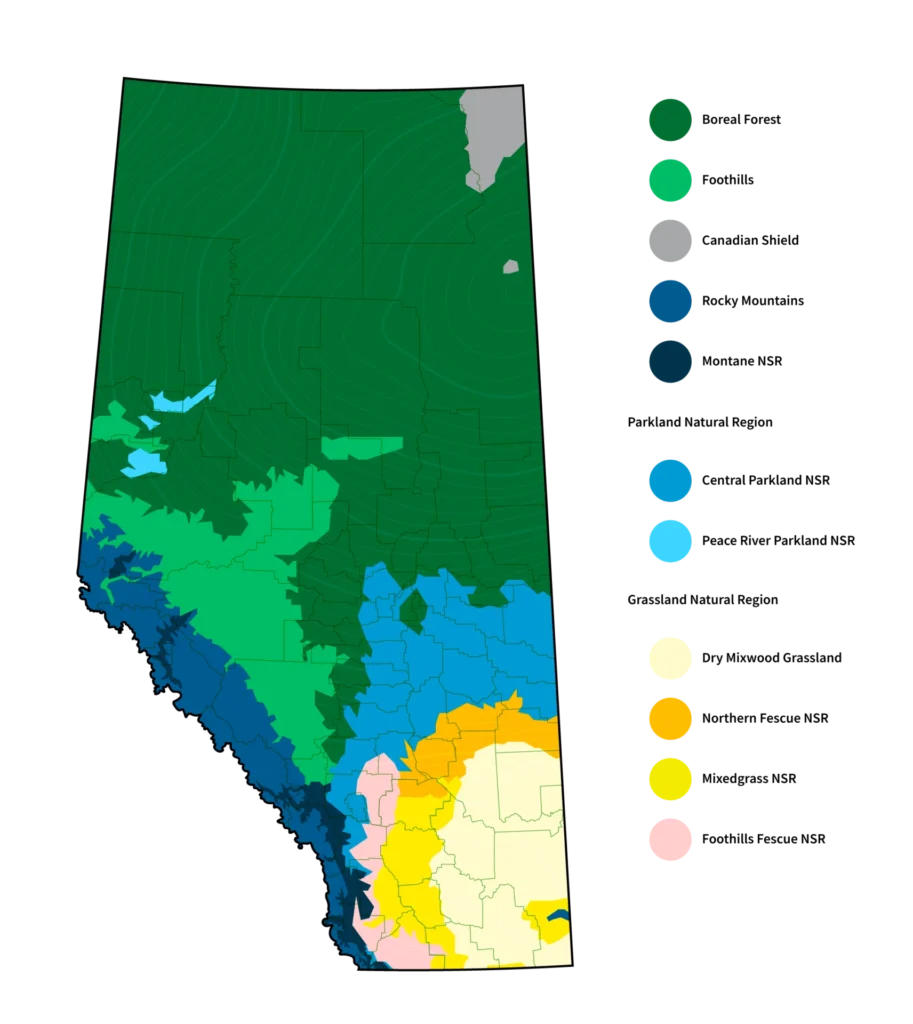

About 75% of Alberta’s species at risk are found in the grassland and parkland regions. These regions make up the bulk of Alberta’s agricultural farmlands. As stewards of these lands, producers are in a unique position to help maintain and protect the habitat of these species at risk.

Using the Habitat and Biodiversity Assessment Tool as part of your EFP can bring you further insight into the beneficial management practices you are already doing to support habitat and suggestions of new practices that could further enhance biodiversity on your land.

We would like to express our gratitude to everyone who made contributions to the development of this tool. See here for a detailed listing of acknowledgements.

Our province is home to a diverse range of landscapes and habitats. The agricultural regions are particularly important for biodiversity and providing habitat to many of the province’s species at risk. As a farmer or rancher, you play a key role in making management decisions that can impact Alberta species’ habitats.

There is a symbiotic relationship that happens when you support habitat for species at risk on your farm or ranch. Depending on the species found on your lands, they may contribute to keeping pests in check, maintaining soil health, supporting ecosystems and increasing biodiversity.

The Habitat & Biodiversity Assessment Tool assesses your land for the potential presence of 90 different species at risk based on location and habitat features. After completing the tool, you will be provided with a customized list of recommended stewardship opportunities to support habitat and biodiversity on your land.

I feel responsible for good stewardship and the EFP process is part of building a legacy.

Denis Kennedy, retired agrologist

Supporting habitat for species at risk needn’t be difficult. In fact, you are probably already doing it. Pasture management, leaving marginal lands alone, maintaining and restoring wetlands and being aware of the species on your lands are all part of beneficial management practices that protect habitat for species at risk.

To learn more, take a look at our video collection on each topic.

The Habitat and Biodiversity Tool is part of every Environmental Farm Plan. It is found as one of the chapters in the workbook and provides beneficial management practices you can implement on your farming or ranching operation.

Protecting the habitat of species at risk is not something unique to the Alberta Environmental Farm Plan. There are many organizations that are also doing great work to promote habitat conservation and biodiversity. At Alberta EFP, we work in tandem with such organizations to increase awareness about Alberta’s species at risk.

Use the below tabs to find examples of species at risk that occur and a stewardship opportunity that can support their habitat in the natural regions and sub-regions across Alberta.

Photo credit: Jason Headley

Found across the province, the Common Nighthawk is known to be calm by day and fly eratically overnight, catching its insect prey. This species can be found in forests, meadows, badlands, near larger lakes and grasslands.

Reduce or eliminate the use of pesticides (herbicides, insecticides, rodenticides, fungicides) using an integrated pest management (IPM) approach. This means using biological, physical, cultural and mechanical pest management like intercropping, crop rotation and mating disruption to help prevent pest populations from causing economic damage and provide pest control options based on actual need. If necessary and as a last resort, choose a rapidly degrading pesticide with low toxicity for non-target organisms, and locate and time application to avoid them. Pesticides can directly harm or kill non-target plants, animals or insects or move through the food chain and contaminate the consumers of these species, bioaccumulate to harm or kill top predators, or indirectly affect the type and amount of food available to them (e.g., food available to other insects, birds, bats, and fish). Insectivorous birds like the Common Nighthawk are particularly vulnerable to their impact.

Photo credit: edporopat

The Yellow Banded Bumble Bee can be found anywhere that there is abundant flowering plants. These bees feed on nectar and pollen, vibrating the flower with its wings to release the pollen. Their populations have been decreasing dramatically since the 1990’s. Approximately 50-60% of their range is found in Canada.

Use zero-till or use reduced tillage practices that minimize tillage depth and frequency. Wild bees are among the most important crop pollinators worldwide. They can increase crop yields even when managed honeybees are present. About 80% of Alberta’s native bee species nest in the ground. Many of these nest within one foot (30 cm) of the soil surface. Tillage can physically damage or destroy developing bees, compact their tunnels and nest cells, or expose developing bees to pests, diseases and changes in moisture and temperature.

Olive-sided Flycatchers are tenacious, protecting their nests, which are built in mountain forests and wetland landscapes. They are often found in dead stands and where forest fires have cleared the landscape to easily catch insects.

Beavers are incredible engineers of habitat. The ponds they create and the areas they flood provide habitat for a high diversity of wetland and riparian related species, including the Olive-sided Flycatcher that uses the open areas above water to hunt insects and those tall snags as singing and foraging perches. Beavers can also help mitigate the impact of droughts through surface water retention behind dams, shallow groundwater storage and slow release throughout the season that contributes to enhancing downstream flows. Where beavers can cause flooding problems, consider installing a beaver deceiver or a beaver baffler or Clemson pond leveler.

Photo credit: Jason Headley

Boreal Toads have sensitive skin, making them excellent indicator species. Indicator species are helpful to show the quality of a given ecosystem, since they are sensitive to potential contaminants. When present, they show that the system is in relatively good health! They are nocturnal feeders and help to transfer nutrients from aquatic to upland ecosystems.

Avoid draining, cultivating, damming, dredging, or infilling permanent, non-permanent, and ephemeral wetlands, potholes, sloughs, ponds and streams; building roads through them, siting dugouts within them, recontouring the land around them, and other activities that may affect water flow, water availability, and water quality in the watershed. Keep as large a vegetation buffer as possible (100 – 650 ft; 30 – 200 m or more) from the water’s edge and maintain downed logs, bark and other coarse woody debris within them, especially large-diameter pieces in various stages of decay. In pastures, consider using pipelines to distribute livestock water to troughs or waterers from a good well or waterbody.

Photo credit: Jason Headley

Barn Swallows reuse nests from previous years, which aids yearling females in selecting nest sites. This practice allows for earlier breeding and higher reproductive success, enabling multiple broods annually. Nests can be reused within a breeding season or in subsequent years, even if left unused for a year. Additionally, Barn Swallows, being insectivorous, can help control insect pests in agricultural areas.Learn more

Do not remove Barn Swallow nests from structures during or after the breeding season. The Barn Swallow breeding season is approximately May through mid-August.

Photo credit: Tomas Nevesely

Often growing as a single tree, Limber Pine can live for 1000+ years in the right coditions. It is an early establisher after disturbance and is a keystone species, important for the diets of mammals and birds alike. Whitebark Pine will grow in mixed stands, and as elevation increases, it can be found growing in isolated clumps, surviving in high elevation where other species cannot.

Strategically place salt, feed supplements, water troughs, fences, corrals or other improvements at sites that draw livestock away from Limber Pine or Whitebark Pine stands. Use existing pathways to direct livestock movement. Monitor these areas for livestock damage and consider installing fences or drift fencing to guide livestock towards pasture that is more resilient to grazing. Consider directing cattle towards other areas for shade such as Douglas-fir or aspen or create some alternate shade.

Photo credit: Jason Headley

Preventing or restricting direct livestock access to surface water reduces shoreline erosion and nutrient input into the water, benefits water quality and the habitat of aquatic species, and allows native plants to establish on the shore, grow, and contribute to wildlife habitat and the other important functions of riparian areas. In turn, this increases life of constructed dugouts and ponds, reducing cleaning and re-excavation costs; promotes herd health and safety leading to improved animal performance and weight gain. Learn more

Reduce the impact of livestock on dugouts, streams, wetlands (sloughs/potholes), lakes, and their adjacent riparian areas. Consider providing off-stream or off-site livestock watering areas. Alternatively, establish graveled or hardened ramps at strategic access points along the waterbody or dugout. In both cases, fencing may or may not be necessary. The ramp should be constructed at a location that requires the least amount of bank modification, limits the amount of natural damage (including on fish spawning habitat), and has good access to the water supply. Contact Alberta Environment and Parks prior to commencing any work on wetlands (sloughs/potholes) or waterbodies.

Photo credit: Michelle Anne Nyss

anada warblers primarily feed on spiders and insects in the shrub layer and nest on or near the forest floor, hidden by dense vegetation. Habitat loss due to drained swamp forests and agricultural expansion increases nest parasitism from Brown-headed Cowbirds. Livestock grazing harms the shrub layer and forest floor. Forest fragmentation from roads and trails creates more edges, reducing suitable habitats and increasing vehicle collision risks. Learn More

Retain unharvested stands (large -preferably 250 ac; 100 ha or more) of old deciduous-dominated forest with a complex understory. Avoid creating roads or trails and expanding agricultural land into those stands, including grazing cattle into the understory and draining swamps. This includes forested or shrubby swamps, riparian woodlands, and brushy ravines.

Photo credit: Vladislav T. Jirousek

Wolverines and other native species thrive in roadless natural habitats. Roads contribute to direct mortality (roadkill), habitat loss and fragmentation, spread invasive species, and create barriers for wildlife. Many species, including wolverines, avoid roads, leading to displacement and disrupted movement. While some animals may be drawn to roads for food or easier travel, this increases their risk of vehicle strikes. Additionally, new roads provide human access, potentially stressing local wildlife populations.

Avoid building roads and trails in natural habitats. If necessary, undeveloped trails are less detrimental to wildlife than built-up, graded or paved roads. Limit the number of trails and ensure that vehicle use is restricted to them.

Photo credit: Jason Headley

The native prairie ecosystem is one of the most endangered habitats globally, essential for maintaining diverse plant and animal life, including the Prairie Rattlesnake. Healthy prairies offer numerous benefits, such as providing quality forage for livestock, preventing soil erosion, managing water resources, cycling nutrients to reduce fertilizer needs, controlling weeds, and supporting wildlife, including pest predators. They also contribute to carbon capture and exhibit resilience against environmental stressors.

Retain your native prairie habitats. These include naturally occurring grasslands, wetlands (permanent and temporary), riparian areas, coulees, badlands, shrublands, cottonwood forests, aspen forests, sandhills, etc.

Photo credit: Jason Headley

American badgers play a crucial role in prairie and open forest ecosystems as predators of rodents like Richardson’s ground squirrels, helping to control their populations. Their old burrows benefit species at risk, such as Swift Foxes and Burrowing Owls, making them a “keystone species.” Badger tunnels also aerate soil, enhance organic matter formation, and improve water penetration, resulting in greener grass around their burrows compared to the surrounding area. Learn more

Tolerate badgers. Badgers occur in perennial grassland, shrubland and open forest areas, including ditches, fencerows, field borders, hedgerows, and other sites that enable burrowing and support burrows that won’t collapse.

Photo credit: Lev Frid

The Sprague’s Pipit is difficult to find unless it is singing, often flushing in grasslands and prairies from underfoot. The species is considered a high conservation priority because its habitat (prairies/grasslands) is often disturbed.

Use light to moderate grazing in pastures to promote a healthy range and use salt blocks and watering sites to create variability in grass height and litter cover.

Photo Credit: Jay Pierstorff

Many raptors, including the Prairie Falcon, are likely to abandon their nest and leave the area when disturbed. As they prey on ground squirrels during the breeding season, they provide a natural rodent control service at no cost.

Reduce the impact of livestock on dugouts, streams, wetlands (sloughs/potholes), lakes, and their adjacent riparian areas. Consider providing off-stream or off-site livestock watering areas. Alternatively, establish graveled or hardened ramps at strategic access points along the waterbody or dugout. In both cases, fencing may or may not be necessary. The ramp should be constructed at a location that requires the least amount of bank modification, limits the amount of natural damage (including on fish spawning habitat), and has good access to the water supply. Contact Alberta Environment and Parks prior to commencing any work on wetlands (sloughs/potholes) or waterbodies.

Photo credit: Tomas Nevesely

Often growing as a single tree, Limber Pine can live for 1000+ years in the right coditions. It is an early establisher after disturbance and is a keystone species, important for the diets of mammals and birds alike. Whitebark Pine will grow in mixed stands, and as elevation increases, it can be found growing in isolated clumps, surviving in high elevation where other species cannot.

Strategically place salt, feed supplements, water troughs, fences, corrals or other improvements at sites that draw livestock away from Limber Pine or Whitebark Pine stands. Use existing pathways to direct livestock movement. Monitor these areas for livestock damage and consider installing fences or drift fencing to guide livestock towards pasture that is more resilient to grazing. Consider directing cattle towards other areas for shade such as Douglas-fir or aspen or create some alternate shade.

Photo credit: Richard Damian Knight

The Short-eared Owl’s ear tufts are often invisible but they use their acute sense of hearing for hunting their prey. This species is often found in open spaces like grassland habitats.

Delay haying or mowing all or parts of a field as late as possible (preferably until after end of July). Choose fields that are 15 ac (6 ha) or more in size and/or fields that contain grass hay that heads later than usual due to damp soils, cooler climate, or late-maturing varieties. Harvest fields back and forth from the inside outward or farther from and moving toward adjacent grassland rather than in circles from the outside inward. Use a flushing bar during haying.

Photo credit: Jason Headley

Synthetic pesticides and fertilizers can directly or indirectly, singly or in combination affect the health of a wide range of terrestrial and aquatic organisms and the role they play in the ecosystems. Pesticides, particularly neonicotinoids, pose significant risks to non-target species and ecosystems due to their toxicity and persistence. They can harm or kill beneficial insects like pollinators or other invertebrates at the base of the food chain and disrupt natural processes essential for ecosystem health. Widespread use, including preventive measures like seed coating, leads to their inevitable spread into non-target habitats. However, adopting Integrated Pest Management (IPM) strategies reduces pesticide reliance and promotes natural pest control methods, benefiting soil health, soil microbiology, pollinator populations, biological pest control, and potentially increasing yields while mitigating pesticide resistance.

Reduce the use of synthetic fertilizer and pesticides (herbicides, insecticides, rodenticides, fungicides) and use an integrated pest management (IPM) approach. This means using biological, physical, cultural and mechanical pest management like intercropping, crop rotation and mating disruption to help prevent pest populations from causing economic damage and provide pest control options based on actual need. If necessary and as a last resort, choose a rapidly degrading pesticide with low toxicity for non-target organisms, and time and locate application to avoid them. Do not apply pesticides or fertilizer near the water’s edge and allow a buffer (100 to 650 ft [30 – 200 m] or more) of native plants around wetlands and waterbodies. Avoid or minimize use of neonicotinoid insecticides.

Photo credit: Bat Conservation International – J. Scott Altenbach

The Northern Myotis looks simiar to the more common Little Brown Myotis, and is threatened by white nose syndrome, which disrupts their hibernation cycle. Most bats use echolocation to catch their food mid air, but this species has been kown to scoop its prey from treees and leaves too.

Retaining shelterbelts or hedgerows/connectivity: promote habitat connectivity. Bats use these lines of vegetation along field and road margins as protected areas of cover during flights between roosting and foraging or drinking habitats. These features also provide roosting habitat when large trees are retained. See “Shelterbelts for Livestock Farms in Alberta Planning, Planting and Maintenance” for recommendations.

Photo credit: Jason Headley

Intact old coniferous or mixedwood stands offer multi-level habitats for birds, bats and mammals: 1) large deciduous damaged trees and snags provide cavities, cracks, broken tops and peeling bark for barred owls, woodpeckers, and bats to breed or roost in, 2) foliage from large coniferous trees provides cover for nesting warblers and an abundance of caterpillars, budworms and other insects and spiders to feed on, 3) lower spruce and fir trees or limbs provide cover for owl chicks, 4) open space under the trees allows owls to fly and hunt prey from the woody debris on the ground, and 5) ecologically intact areas, where prey and other carnivore species are common and diverse also attract the elusive wolverine.

Retain stands (of any size, but >250 ac or >100 ha are better) of mature/old (>100 years old) coniferous or mixedwood forest with large diam trees (live or dead; e.g., >20 in [50 cm] white spruce/balsam fir; >8 in [20 cm ] paper birch; >14 in [35] cm aspen/poplar). Avoid building roads in forests but if a road is necessary, it should be placed in younger stands and be temporary. Avoid clearing trees or digging dugouts that attract cattle. Leave deadfall, leaning trees or cover plants. Provide an alternate shelter for livestock.